Reel Rundown: Conspiratorial documentary ‘American Conspiracy: The Octopus Murders’ goes many places, but also nowhere

In his 1966 film “Blow-Up,” the great Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni tells a tale that explores the dangers of looking too far into in. David Hemmings plays a photographer obsessed with solving what he suspects is a murder, only to end up throwing an imaginary ball to a couple of mimes in a park.

For movie fans of the time, that metaphorical ending blew more than few minds.

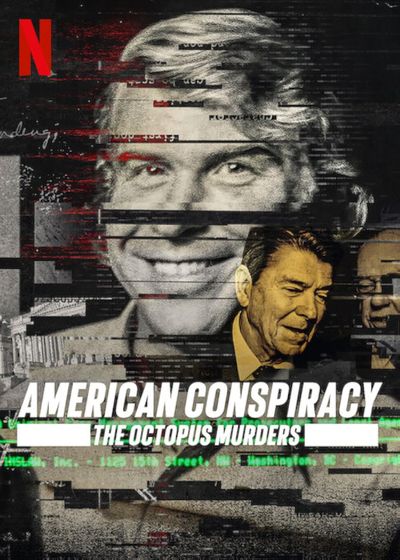

The theme of Antonioni’s film could apply equally to a Netflix documentary series titled “American Conspiracy: The Octopus Murders,” though with far less impact. Directed by Zachary Treitz, the four-part series is the television equivalent of seeing shifting patterns in a spider web and thinking they represent something sinister.

The central piece of the series is the 1991 death of freelance investigative journalist Danny Casolaro, whose blood-drenched body was discovered in the bathtub of a Martinsburg, West Virginia, hotel room. Casolaro had been working for years on what he considered one of the biggest scandals in American political history.

Director Treitz centers his film on Christian Hansen, another freelance journalist who stumbles onto Casolaro’s death, which officials quickly ruled a suicide. However, Casolaro’s friends and family, particularly his brother Tony, believe that he was on to something big and was murdered to keep him quiet.

Pretty soon Hansen is intrigued, not just by the contradictions of that ruling but also by the story that Casolaro was investigating.

In short, Casolaro was looking at a complex miasma of connections involving insider information, political corruption, secret files and greed – the fabled treasure of anyone looking to get at the heart of a conspiracy theory.

In Casolaro’s case, that theory concerned a legal and financial fight between a computer company (INSLAW) and the federal Department of Justice. The company had developed a software program (PROMIS) designed to track criminal activity and sold it to the DOJ. But for some reason the feds stopped payment, ultimately forcing INSLAW into bankruptcy.

Casolaro suspected that the government had stolen the program and planned to sell it to other countries, enemies and allies, as a means of spying on them. And that the deal was connected to major government figures.

Over the course of the four episodes, Treitz – while employing a blend of real-life and re-created scenes – follows Hansen as he shifts through dozens of boxes of notes and seeks out and interviews a number of people. Many are aboveboard, but some are clearly sketchy. And one of the sketchiest is Michael Riconosciuto, a guy who spent years in prison and who claims to have damning information.

In the end, what Riconosciuto tells Hansen, and Treitz, goes nowhere – much like the series itself. What’s intriguing about Treitz’s documentary is that there’s just enough factual references – a linking to the real-life Iran-Contra scandal, for example – to string things along.

As for Casolaro’s death, it’s never made clear what happened. Was there a larger conspiracy and was he murdered to cover it up? Or did he reach a dead end and, facing failure after years of effort, decide to end things.

Treitz makes it clear that Hansen and another journalist, Cheri Seymour, chose to quit long before reaching that point.

He might just as well have quoted Shakespeare, whose King Lear at one point declaims, “That way madness lies.”