Spokane art advocate, trailblazer Lila Girvin dies at 95

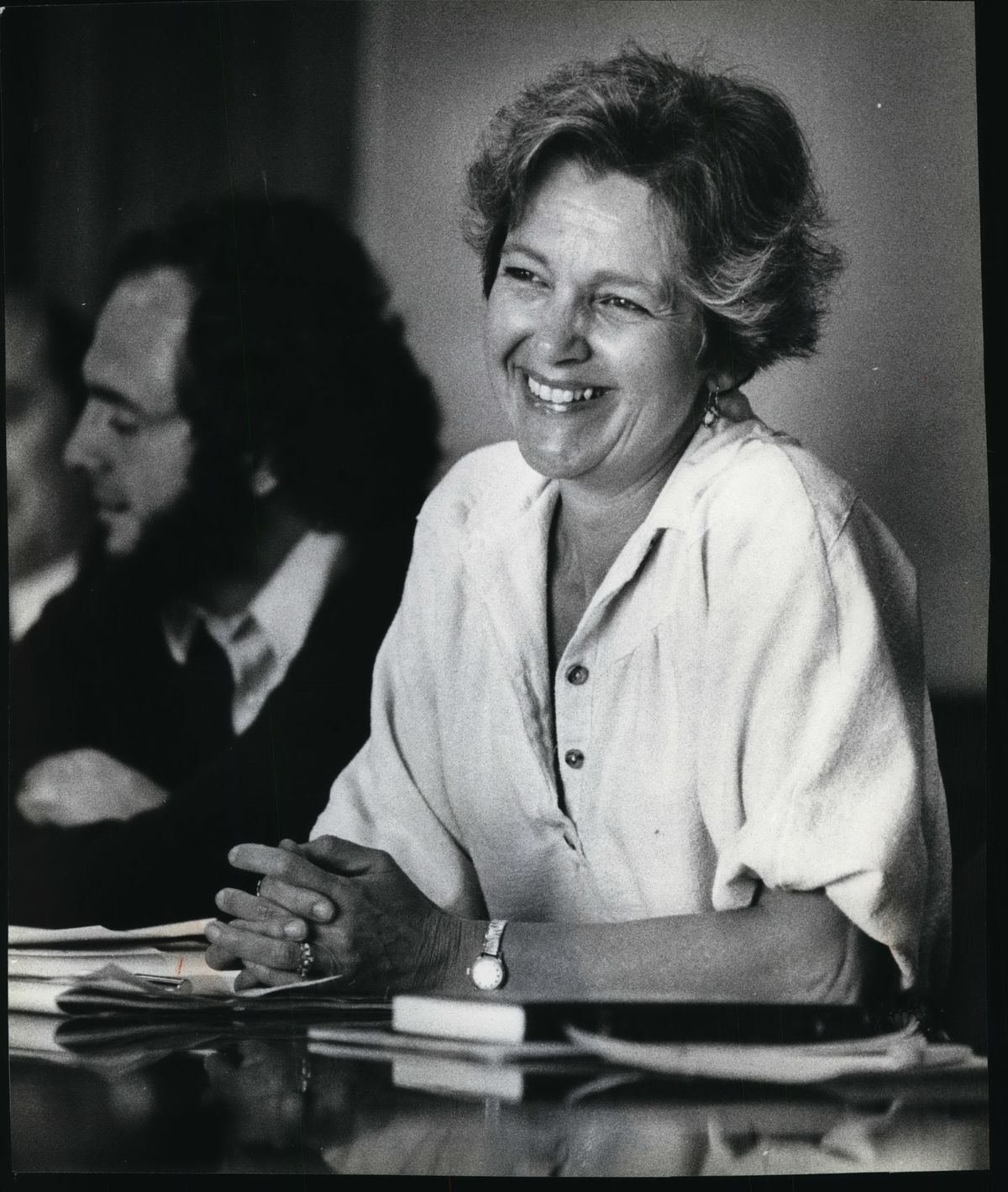

Artist Lila Girvin poses for a photo at her home on Sept. 23, 2022, in Spokane. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Lila Girvin, a local painter who gave her art, heart and soul to support local creatives and arts organizations, died Jan. 9 at her South Hill home surrounded by family. She was 95.

The spirited arts champion was married for 73 years to Dr. George Girvin, a retired surgeon who died six months ago at age 96. The Girvins filled their seven decades together with countless local art shows, classical concerts and political campaign events as Spokane grew from a sleepy town, pre-Expo ’74, to the creative regional hub it is today.

The couple quietly donated to theaters, music groups and arts education programs, to encourage Spokane’s underfunded artists and local nonprofits to keep going. They gave to left-leaning local political campaigns and candidates, especially those who pledged to move Spokane forward and to protect the natural environment.

Just three months ago, Spokane Arts honored Lila with a lifetime achievement award. Nearly 50 years ago, the soft-spoken woman with a steely resolve helped start the first Spokane Arts Commission.

Lila also volunteered as a trustee of the former Allied Arts of Spokane and was the first woman to serve on the Boundary Review Board after she complained to the governor about the lack of city planning and possible environmental damage to the greater Spokane community back in the 1970s.

In the 1980s, she volunteered for the Spokane Symphony and became chair of the Evergreen State College board of directors.

The petite, gray-haired woman who was quick with a smile or a chuckle was known for more than her heart. Lila also displayed a massive talent with oils on canvas.

Her mastery was recognized by the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture’s Wes Jessup on the first day he arrived to work seven years ago as its then-new executive director. After stumbling upon a set of Lila’s paintings in a hallway, he was struck by the skill and depth of her works. She was already a well-established painter, with her ethereal pieces included in the MAC’s permanent collection, at the Jundt at Gonzaga University and in private regional galleries. She also was a purchase award winner for the Washington State Art Exhibition in Wenatchee and the Women Painters of Washington at the Seattle Art Museum.

Almost immediately, Jessup offered Lila a prestigious solo exhibition, but she turned him down, claiming she was not worthy of the fuss. Perhaps her signature modesty was the reason she demurred, or maybe she was secure in her own standing among the giants in the abstract expressionist movement of the Pacific Northwest. It took Jessup five more years to finally convince Lila to allow the MAC to showcase her breathtaking 60-year retrospective. “Gift of a Moment: Lila Shaw Girvin,” opened to a grateful public at the MAC in October 2022.

Growing up in Denver, Lila’s artistic interests were more musical rather than visual. She played classical piano, and as a teenager landed a job entertaining visitors at the Grand Canyon’s North Rim lodge one summer. After graduating from the University of Denver in 1951, she married a charming and playful medical school student, George.

The couple moved several times – Detroit, Michigan; San Antonio, Texas; and Trenton, New Jersey – as George trained as a surgeon for the U.S. Army. Their last stop before Spokane was Seattle, where Lila recalled “spectacular beauty, mist and rain, mild temperature, trees, lushness and the sea.”

In Seattle, Lila began raising the first of their four boys, and during those busy years, found her footing as a painter, using the top of the dryer as her worktable since their home was so small. She studied and worked with famed Pacific Northwest painters Kenneth Callahan (1905-86) and Mark Tobey (1890-1976).

After five years in Seattle, where Lila formed key relationships at the Frye Museum, the couple moved to Spokane in 1958 so George could start his medical practice. They happened upon a community of neighbors on the South Hill who were steeped in architecture and art, including the families of progressive midcentury architect Tom Adkison and artist Harold Balazs.

Ever curious and always searching, Lila created a studio in her backyard where she could explore her art. She liked working on the floor where she could move thin layers of paint around without fighting gravity. The works she produced were great washes of color, exciting and ever-changing. Her path was reminiscent of some of her peers in the abstract expressionist movement of the middle of the last century, such as Helen Frankenthaler.

Lila always started a painting wondering what the canvas would reveal to her about her world, her own mind and her own emotions, Lila told The Spokesman-Review in 2022. She was always searching for light.

That gentle philosophy, the search for light, permeated all of Lila’s oil paintings, and indeed, her life. Among other inner journeys over the years, she publicly protested the Vietnam war, joined a women’s consciousness raising group, and eventually sought spiritual guidance at the Unitarian Church.

Along the way, she and George raised their sons, each boys’ accomplishments as startling as their parents – Timothy, the design and advertising wiz; Robert, the doctor; Jonathan, the musical theater producer; and Matthew, the program officer for UNICEF.

But even with all the light, came darkness. In 2001, Matthew was killed in a helicopter crash while working for UNICEF to aid starving children in Mongolia.

Despite the impossible blow, Lila’s art never wavered. She continued to create, and to focus on helping others, as Matt did in his lifetime.

Ever active, Lila played tennis and skied through her 80s. She was playing piano in her 90s. She is survived by her sons Tim, Rob (Lori) and Jon, grandchildren Madeleine, Gabrielle, Kellen, Logan and great -grandchildren Isaiah and Ellis.

Lila’s son Tim wrote in a recent personal blog: “When I was in Kindergarten, I have a specific memory of being instructed in ‘how to fold and cut paper to make a Christmas tree.’ Of course, I didn’t do what I was asked. And I was scolded by the class teacher in a way that I remember as distinctly tear-inducing. Coming home, Mom said, ‘You made the tree in your own way, and that’s just fine – it’s beautiful.’

“… It was my mother that instilled the creative instinct, a constant hungering after exploration, looking into the deeper side of things, investigating and exploring the other side. Not that – which is on the surface – the fundamentally obvious, but rather what’s underneath.”

Throughout her career, marriage and motherhood, Lila kept that curiosity. Friends and admirers often asked how Lila managed to keep her gentle brightness, her focus on life’s humor, beauty and spirituality.

She once said: “I have no secrets, and I struggle like everyone else.”

But upon further reflection, Lila confessed to one guiding principle: “I have to seek the light in my paintings, as well as in myself.”