Showing his age

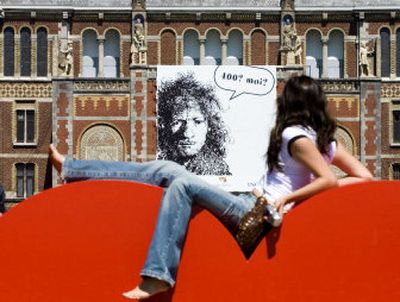

AMSTERDAM, Netherlands – Rembrandt’s earliest self-portraits show a curly-haired, full-cheeked young man of 23, full of confidence, clad in dress above his station, literally wearing his ambition on his sleeve.

By the time we see his haggard face 40 years later – with dozens of portraits in between – we feel as though we know him like an uncle.

Still, despite that sense of familiarity, Rembrandt has remained a historical mystery.

For centuries, his personal story was shrouded by the romanticism of admirers who perpetuated the legend of an artist toiling away in obscurity in an all-consuming quest to unravel the secrets of the soul.

But as the Dutch celebrate his 400th birthday on Friday, some of those myths are being demolished.

Compared with contemporaries such as Vermeer, Rembrandt’s life is surprisingly well-documented – with his bankruptcy and court cases providing a treasure trove of detail.

“What emerges is an unpleasant character, a cantankerous man who, at least on one occasion, showed extraordinary cruelty,” says Rembrandt historian Gary Schwartz, referring to the artist’s mistreatment of his mistress, Geertje Dircx.

Rembrandt’s work and his life are open to the public as never before during the yearlong festival “Rembrandt 400.” Nearly 100 oils have been loaned to Dutch museums, adding to the 49 permanently housed in the Netherlands, and a series of spectacular exhibitions is highlighting different aspects of his work.

His birthday also is being celebrated with commercial silliness – Rembrandt spaghetti, Rembrandt chocolate and Rembrandt wine. Tourists photograph themselves standing amid life-size bronze re-creations of his most famous painting, “The Night Watch,” in Amsterdam’s Rembrandt Square.

The Rembrandt Ice Sculpture Festival drew 280,000 visitors. “Rembrandt the Musical,” premiering in Holland on Friday, focuses on his relations with the three women in his life.

“My hope for the Rembrandt year would be that somehow we would become free of images, that we look with fresh eyes,” said Ernst van de Wetering, head of the Rembrandt Research Project and widely considered the world’s foremost Rembrandt scholar.

Van de Wetering dismisses the notion of Rembrandt as the impoverished artist driven to heights of creativity by his fiery emotions. Rather, he conceptualized his craft dispassionately, in a constant search for greatness.

His inventiveness and originality did not come without hard work. He made small studies of light and shadow, of facial expressions – often his own – before incorporating them into historical works or biblical allegories.

Schwartz, an American who has lived in Holland more than 50 years, said the vicious side of Rembrandt’s character was long overlooked by art historians. He said it really shocked him as he did research for his 1984 book, “Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings,” based on some 500 documents from Rembrandt’s life.

Schwartz said he identified 25 conflicts the artist had with his family, creditors, patrons – even sitters who claimed he cheated them.

But his new study, “The Rembrandt Book,” published in Holland this month and due in the United States in October, takes a softer view.

“I decided he was incapable of compromise,” Schwartz said. “This caused him great problems, but it was one of the qualities that benefited his art.”

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born in Leiden, 20 miles south of Amsterdam, the son of a miller. He moved to Amsterdam in 1631, where he married Saskia van Uylenburgh, the cousin of an art dealer who introduced him to wealthy clients.

After Saskia died in 1642, Rembrandt bedded his son’s nursemaid, Geertje Dircx, but discarded her for his 23-year-old housekeeper, Hendrickje Stoffels. Dircx took him to court for breach of a promise to marry her, but Rembrandt took his vengeance by testifying that she was unbalanced and had her committed.

Rembrandt was never the poor struggling artist. He won fame from an early age and commissions kept flowing.

But he was a miserable money manager and profligate spender. He went bankrupt and was evicted from his home in 1658. Four years later, he even sold his wife’s grave site to pay off debts.

He painted self-portraits throughout his life, not to satisfy his ego or to explore his soul, but because he was a name brand and the works sold well.

Not only has Rembrandt’s character come into doubt, but so has his inventory. Even now, uncertainty remains about dozens of paintings that may or may not be his.

A 1935 inventory listed 611 Rembrandt oils, but the Rembrandt Research Project has whittled that down by about half. Yet even van de Wetering changes his mind sometimes.

New works are still being discovered. Two, borrowed from Warsaw Castle for exhibit, were long attributed to “Rembrandt’s studio.”

After they were cleaned of grime, X-rayed and chemically tested while still in Poland, van de Wetering announced earlier this year that they came from the master’s own brush.